EQ-i 2.0 Case Studies

This page includes 9 unique case studies spanning corporate executives, community leaders, athletes, and those in career transition presented by top emotional intelligence experts and consultants. Each case study presents the EQ-i® 2.0 profiles and is supplemented with the client’s background information, interpretation, and insight into the coaching and development strategies used. The profiles, the collateral assessment information, and biographical information have been altered to protect the identity of the client and to adhere to acceptable ethical standards of psychological assessment. The results are discussed and a brief interpretation of the results is offered. Each case emphasizes the composite scales and subscales and illustrates the importance of looking at subscale scores in isolation as well as the interactive implications of subscales. Each profile graph is derived from the EQ-i 2.0 Workplace Report.

Submitted by: Brett Richards

Client Background

The client is the General Manager (GM) of a high-growth subsidiary of a large organization in the Health Sector. The organization is experiencing tremendous growth and is feeling the effects of that success in terms of resource stretch. It is a fast-paced environment and the whole organization is working long hours to keep up with the work. The client has been very successful at leading smaller niche enterprises with separate P&L’s within larger global organizations for the past 7 years. The client is the type of leader where people gravitate to his integrity and values-based leadership style.

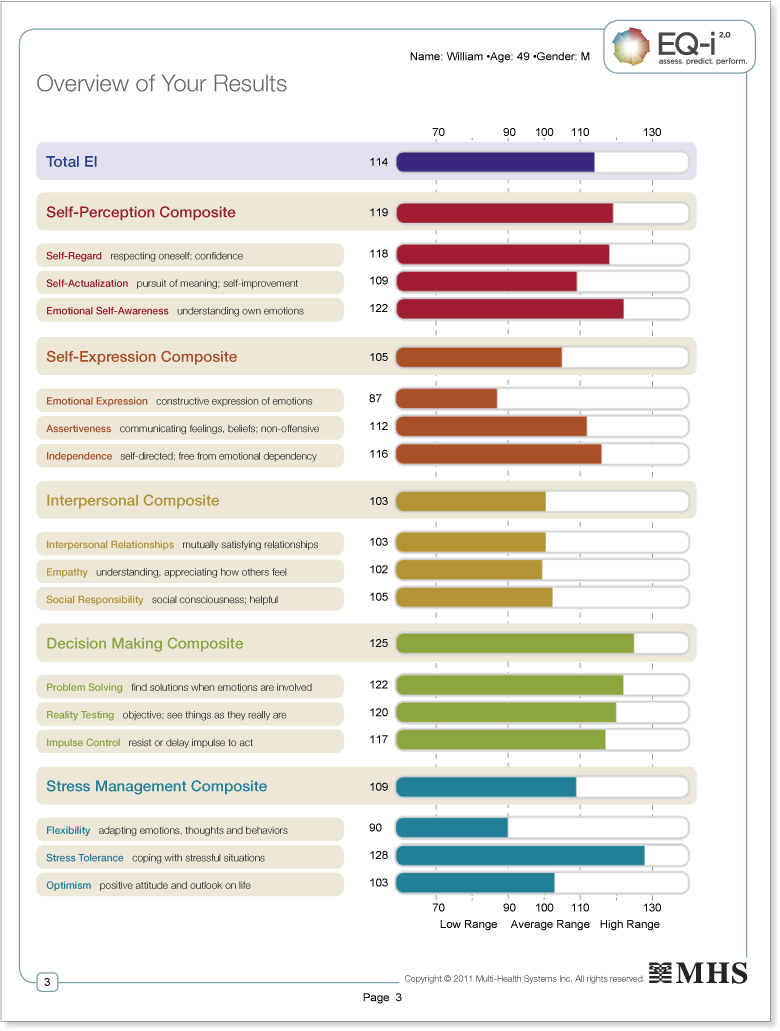

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

The client’s Total EI score (114) is well above the average range and represents a well‑developed overall level of emotional and social functioning. Experience and research has shown that more effective leaders typically possess above-average skills in emotional and social intelligence, which is the case with this client who has proven to be successful in several top leadership positions. While it is helpful to know the overall EI score, it is important to look at the composite and subscales to provide a more nuanced understanding of the unique strengths and areas of potential development for the client.

The five composite scales show enhanced abilities in Decision Making (125), Self-Perception (119), and Stress Management (109), which indicate a strong understanding and ability to monitor the way in which emotions participate in the decision making process. It also indicates an ability to look at decisions objectively, resisting the temptation to act rashly in difficult circumstances. This ability is particularly useful in a stressful, entrepreneurial start-up environment where change is the constant and ambiguity arises on a daily basis. The other composite scales indicate relatively lower scores, although all remain slightly above the average subscales.

A closer look at the subscales indicates a leader who possesses a high degree of confidence (Self-Regard) and self-awareness (Emotional Self-Awareness). He is self-directed (Self-Actualization, Independence) and likely thrives in complex and stressful environments (Stress Tolerance) that require multiple strategic decisions on a regular basis (Problem Solving). This leader is very comfortable with getting his point across while meeting his needs in such a way that preserves rather than damages relationships (Assertiveness and Interpersonal Relationships).

Coaching Approach & Development Strategies

While the GM has many strengths, a few notable areas are worthy of exploration. Generally, this is a leader who actually thrives in and through change and gets bored in an organization that is in maintenance mode. He appears to have a need to significantly improve organizations and the people within them, and this requires tremendous personal commitment and energy (Interpersonal Relationship, Social Responsibility, and Self-Actualization). Currently, his strong dedication and commitment to achieving significant organizational results within a high-stress, high-pressure environment may be taking a toll on his emotional well-being as witnessed by his markedly low (Happiness) score. Furthermore, as highlighted by his low Emotional Expression, he may have difficulty expressing his feelings to others within and outside the organization, which may stultify his ability to elevate his Happiness without focussed effort. Being at the top of an organization can be quite isolating; therefore, I would encourage this leader to seek out a confidante, someone outside of the organization that he can talk to. This is a leader who has strong values and beliefs, which supports his principle-centred leadership approach. However, I would explore situations where this may, at times, potentially come across as being inflexible due to his relatively lower Flexibility score. For example, during strategic conversations, he may appear to be difficult to convince or shift his opinion, which could be frustrating to members of his team who believe in the merits of alternative courses of action that may fall outside of his fixed position or opinion. Further, showing more flexibility in certain situations could serve to enhance relationships, as well as the learning potential of his direct reports. This person, as a leader, may like routine both personally and professionally, finding it difficult to change personal strategies (Flexibility) that have proven successful in the past. It may be that, at this point and time, his “winning strategy” is not working successfully for him, and this may be causing some level of personal challenge. On the other hand, there may be circumstances occurring completely outside of the organization which are contributing to his relatively low state of contentment.

Overall, if this leader can strengthen his ability to share and constructively work through his inner thoughts and concerns more regularly with a trusted coach, he will be better positioned to increase his optimism about the future and feel that he is more on track to achieving his full potential and experiencing a life rich in meaning. Some initial coaching strategies would include raising awareness about how his relatively low scores in Emotional Expression, Flexibility and Happiness are related. For example, with an improved ability to articulate his inner feelings to others, a deeper level of dialogue and insight may emerge which could open up new perspectives and strategies to address issues that may be personally troubling at this moment in time.

Submitted by: Marcia Hughes

Client Background

Gladys is a 57-year-old attorney with a successful track record of building relationships that have resulted in collaborative decisions for resolving community challenges. She has served as a community organizer and has been recognized for her leadership through many awards. Gladys is a positive and upbeat person, someone others come to for support and to renew their energy. She is married, actively volunteers, and is regularly seen at economic development forums, shepherding seniors to special lunches and taking family members to events. Gladys is reliable. As a result of her optimism and overall zeal, it has come to be expected that Gladys is overtly affirming of those she encounters and will openly and enthusiastically greet those she is in connection with, from business colleagues to friends. She grew up in a tough neighbourhood and attributes her skills to good parenting¸ having excellent role models who emphasized the necessity to give back to the community, and an excellent education that empowered her to change her world.

According to Gladys, much of her life is great, but there are circumstances that prove challenging to her and test her EI skill development. For example, Gladys has identified challenges with a cousin who has a difficult personality and needs an unusually high level of support, coupled with her own challenges of a recent marriage to a husband who works a great deal. Both of these circumstances were identified by Gladys as valuable areas to explore in our EQ-i 2.0 debriefing.

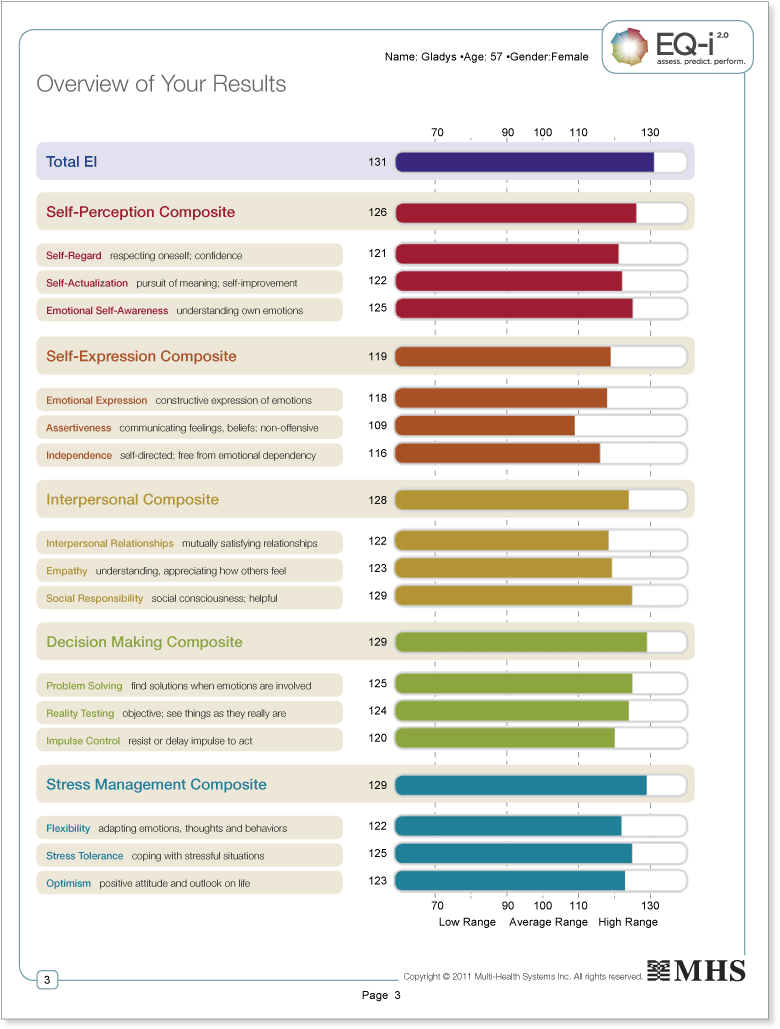

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

The results of the EQ-i 2.0 indicate that Gladys has excellent overall EI skills. Her profile indicates a wide range of abilities, with scores ranging from 109 in Assertiveness to 130 in Social Responsibility. Her positive impression and negative impression scores were acceptable, while her response style was consistent. Gladys indicated she answered questions openly and honestly. With such high scale scores and strong validity, the place to find opportunities to work with her strengths and challenges would be found in her specific item responses. Overall, there is good balance between her skills, although the difference between her lowest, Assertiveness (109), and her strongest, Social Responsibility (130), is large enough to warrant attention. Most of the time Gladys responded to the EQ-i 2.0 using a 1 or 5, suggesting all-or-nothing responding or absolute thinking. Thus, when she answered with a lower score, it helped in finding the specific areas that challenge her.

Coaching Approach & Development Strategies

Gladys wanted to discuss some concerns with individuals, such as her cousin and the relationship with her husband, in connection with her lowest score, which was Assertiveness. She exclaimed she just couldn’t imagine being more assertive as she is quite outspoken; yet she admitted that she’s received feedback that it would behoove her to increase her assertiveness. We explored the apparent contradiction—is she assertive or not? Gladys is quite happy (120), highly empathic (123), and is inclined to take care of others. We found that one low score in Emotional Expression (“When I’m sad, I talk to people about it”) and another in Assertiveness (“I say ‘no’ when I need to”) combine to demonstrate her challenge with Assertiveness. Although Gladys does speak up frequently, enthusiastically and effectively, when she needs to suggest a correction or disagree with someone and knows that it will be hard on the other person, she often softens her message, rescuing the other person from the discomfort. Her own message loses power! Gladys does not tell people when she is sad as they expect her to be the upbeat person who lifts them up. Keeping up the positive face all of the time can be exhausting.

Providing difficult assertive messages is not in accord with the uplifting role Gladys is thoroughly identified with. However, through coaching Gladys realized that she does not want to give her power away and that it can be considerate to tell the truth—provided the truth is said with regard—even if the message is not welcomed at first. Gladys developed an acronym to guide her behavioral change process: AS – Ask, Stop. Ask, allows her to make a request while permitting the recipient an opportunity to respond and work through it. She intends to make the request without softening it to the point of losing her own message. Stopping is even more of a new strategy for her. Gladys is committed to no longer rescuing the listener from the discomfort of the message. She will stop and allow silence, whether for a minute or two in a conversation or for days if the matter requires more time. As a continuous learner, she is eager to start applying her new skills.

In summary, the key steps we took as a part of this coaching process were:

- Identify current life situations that are problematic. This step is critical to keeping the discussion practical and sufficiently concrete to invite lasting behavioral change.

- Tying change to challenges and strengths as identified by the EQ-i 2.0 results is important to remember. Strengths as they appear are often a person’s greatest point of leverage. While discussing key responses in the report, such as her difficulty in saying no and the difficulty in telling others about her challenging emotions, we began tying those answers to her identified problem scenarios. From this specific discussion, we expanded our conversation to a more global discussion of how these behaviors can cause unfavorable results.

- Brainstorm together about ways to make changes. Here, through a trial and error discussion of possible actions, Gladys exuberantly developed her AS strategy. Because she developed it, she is more likely to employ it and make real changes.

Finally, we discussed specifics about applying the change in her responses. She will use the new process as needed, while also taking time at the end of the day to review her responses and notice how well her responses worked for her. - Building the process of reflective self-awareness is tremendously valuable. We talked about her learning as she reflects on this change and then continuing to build her reflective skills as she considers her interactions more broadly. Gladys intends to keep using this AS strategy so it won’t stop after her initial excitement with the strategy.

Submitted by: Dana Ackley

Client Background

Tom is a 40-year-old husband and father of two. Tom is a professional with an advanced degree, who works as a senior executive in a not-for-profit organization, leading a team of five colleagues. Tom has a solid history of success working within organizations. When he attempted to begin his own business, his success was adequate but not outstanding. He found that he missed the connectedness that he felt working for an institution. He returned to his current employer, who asked him to turn around a department currently in disarray.

Tom described himself as highly optimistic with lots of positive emotional energy. He saw himself as skilled in creating harmony within his work team. He succeeded in turning the performance of his department around by using his high level of positive energy and genuine enjoyment of people. However, Tom was also able to articulate limitations in his approach. He said: “I don’t do well with conflict. When someone disagrees, I nod but don’t raise my concerns.” He took the EQ-i 2.0 in order to identify barriers to managing conflict, having tough conversations and making use of “teaching moments.”

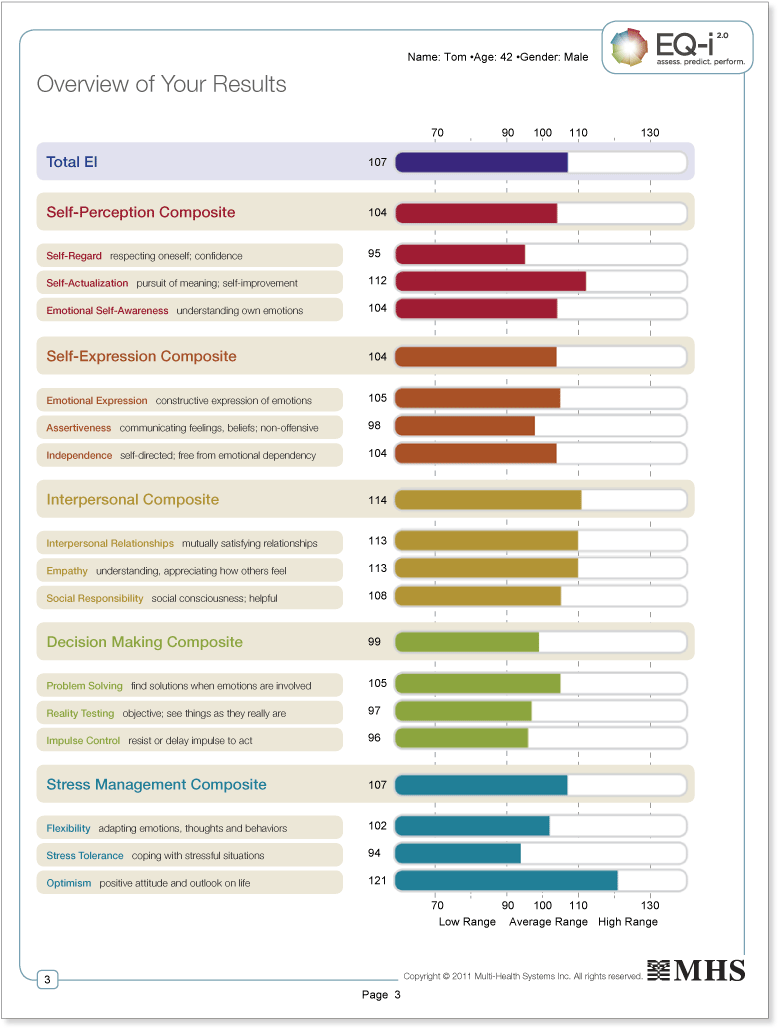

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

All of Tom’s EQ-i 2.0 scores are average or better, consistent with the success he has had in his career and as a leader. While he does not have any low scores, the differences that exist among scores shed light on his strengths and opportunities.

His self-description was highly consistent with his EQ-i 2.0 profile. The Interpersonal Composite shows strong interpersonal skills across the board. He is good with people. His high scores on Optimism and Happiness speak to his ability to create high levels of positive energy that draw others to him, creating a positive context within which he can lead and influence people.

All of Tom’s EQ-i 2.0 scores are average or better, consistent with the success he has had in his career and as a leader. While he does not have any low scores, the differences that exist among scores shed light on his strengths and opportunities.

His self-description was highly consistent with his EQ-i 2.0 profile. The Interpersonal Composite shows strong interpersonal skills across the board. He is good with people. His high scores on Optimism and Happiness speak to his ability to create high levels of positive energy that draw others to him, creating a positive context within which he can lead and influence people.

Consistent with his report of difficulty with conflict, Tom’s scores on Assertiveness and Self-Regard are relatively low. To avoid conflict, he too often puts others’ wishes ahead of his own, rather than strive for a functional balance. This pattern has an erosive effect on Tom’s Self-Regard.

His relatively low score on Stress Tolerance signals the anxiety he reports during conflict. Impulse Control is also relatively low, consistent with anxiety impacting decision making about what to do when faced with conflict. Interestingly, once Tom gets some distance from the event, he begins to think more clearly, using skills consistent with his high score on Optimism. Instead of staying anxious, he begins to think in resilient ways. He thinks about possibilities instead of barriers.

In discussing his positive attitude, he noted “I can be kind of myopic sometimes.” This reflection is consistent with his relatively low score on Reality Testing. He tends to wear rose-colored glasses, missing signs that might warn him that a conflict may be on the horizon. He doesn’t want to see conflict because he has little confidence in his ability to handle it.

Tom has devoted himself to self-development in many aspects of his life. He spent years in foreign countries to learn their languages and cultures. He earned a professional degree for the intellectual development it offered. His high Self-Actualization score is consistent with that history and predicts a positive response to attempts to build EI skills that need attention.

Coaching Approach & Development Strategies

Clearly Tom needs to become more assertive. And he knows it. His barrier has not been that knowledge. Instead, he had not recognized the role that anxiety plays in the process. Review of the EQ-i 2.0 profile helped identify the sequence of denial, recognition of conflict, anxiety, and then retreat. Before he can be more assertive in conflict situations, Tom needs to learn to manage that initial anxious response. Discussing the profile provided us a context within which we could identify the roots of his anxiety over conflict. “Connecting the dots” often removes much of the power of past experiences.

Learning the role of anxiety in his conflict avoidance motivated Tom to build his Stress Tolerance skills, especially within conflict situations. Exercises in the EQ Leader Program Manual (Ackley, 2006) were provided. Once he has built those skills, he will be ready to learn better Assertiveness skills. With the anxiety under control, that is likely to happen fairly quickly for someone with this man’s overall EI skills. And when Tom is ready to focus on Assertiveness, a variety of exercises can provide the necessary framework for development. It is quite likely that as he improves in his ability to manage conflict, his Self-Regard skills will improve largely on their own because he will have more balance in seeing to his needs and those of other people.Submitted by: Hile Rutledge

Client Background

Brian is a successful 41-year-old executive newly hired to a consulting firm that works exclusively with the United States Department of Defence. Most of the people now reporting to Brian are Ph.D. researchers 10 to 25 years his senior. Given Brian’s age, his lack of an advanced degree (he has a Bachelor of Arts in History), and his inexperience with advanced research projects, he feels at times stressed by his senior-level position and its demands. Will today be the day that everyone learns how far in over his head he is? This internal query is one that plays on continuous loop within Brian’s head. Seeing the EQ-i 2.0 as an opportunity to sharpen his self-awareness and relationship building skills, Brian eagerly engages in the EI process.

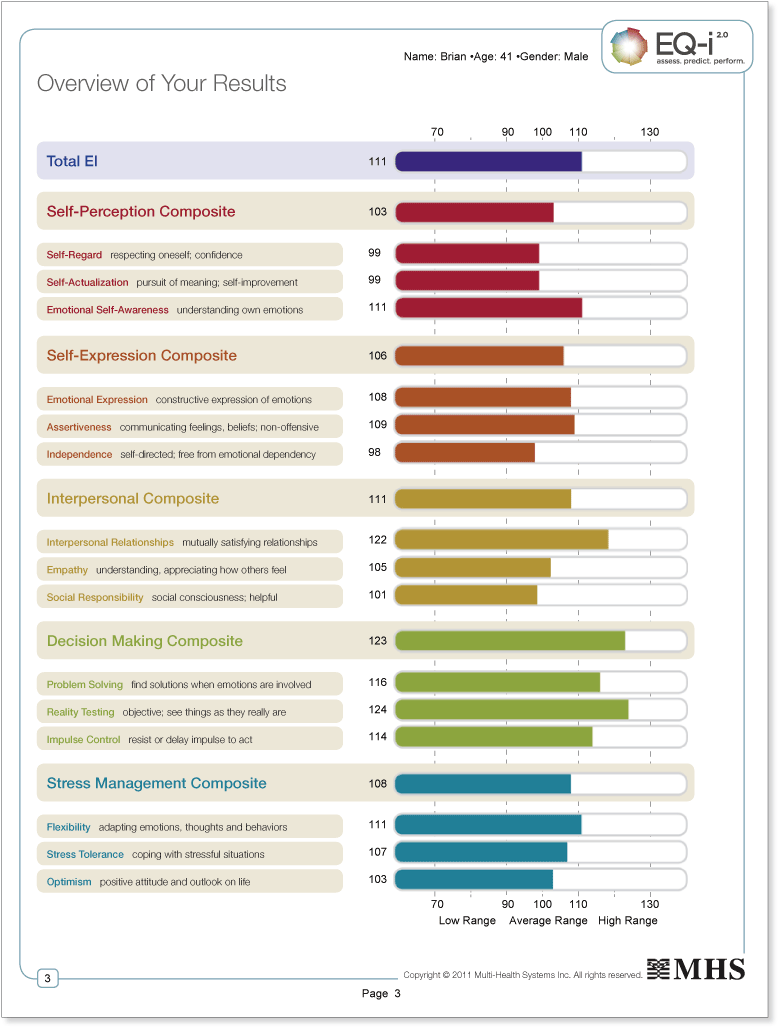

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

To make the EQ-i 2.0 feel less like a report card and more like the spur to a deep, data-driven discussion about self-awareness and self-management, the first step in the feedback process is to define the various elements of the EQ-i 2.0 model by having Brian do a self-assessment as to how often, easily and consistently he engages with each element in his daily life. Low engagement could reflect low skills, but it could also reflect adequate skills in an area seen as unimportant and not often ignored. High engagement could reflect enhanced development and high skills, but it could also indicate over-engagement and a quality or behavior that is over-done or often too intense. Average engagement means the element is used or paid attention to about as much as it is with most people. Average engagement with an EQ element means that there is certainly room for improvement and growth in that area, but there is nothing in average engagement that means that development is required or that this is in any way a liability.

Brian predicted high levels of engagement with Interpersonal Relationship, Reality Testing, Problem Solving and Emotional Self-Awareness; and low engagement with Self-Actualization. All other elements he felt well connected to, but not in a way that would distinguish him from anyone else—so about average. With this self-assessment complete, Brian was now ready to receive and fully understand his EQ-i 2.0 report. Brian’s highest scores—Reality Testing and Interpersonal Relationship and Problem Solving—were not a surprise, but his connection to the EQ-i 2.0 process got a boost from his being able to predict his attachment to these elements.

After noticing these high scores, Brian’s attention was then pulled to some of the lower scores on his report, which did surprise him. Self-Regard and Self-Actualization were among the lowest scores on his report, and while they were (at 99) just under the average, he was surprised by seeing these important elements at the bottom of his line-up. In the discussion that followed, Brian came to realize that in his new environment, in which he was leading so many people a good bit older than he with technical expertise and degrees he did not have, that he was relying on his ability to connect personally and relationship build as a means of management and decision making. And while Brian did this with great frequency and ease, he had a low-boiling fear that he had not pursued enough formal education (in the form of a graduate degree) and/or amassed more research expertise. These fears were evident in his lower Self-Regard and Self-Actualization scores, creating a greater sense of awareness about his otherwise perceived confident and accomplished sense of self.

These realities were adding a new kind of stress to Brian’s professional life, which brought on the biggest surprise of all—a Happiness score that would put him around the bottom third of respondents in Happiness. Long self-described as a happy and funny man, Brian was feeling increasingly disconnected from this personae, and he decided to take steps to correct this disconnect.

Coaching Approach & Development Strategies

Brian decided to use his EI strengths (Interpersonal Relationships and Decision Making) to help him reframe and better engage the EI elements with which he most often struggled—Happiness and Self-Actualization. He decided to reach out and create a close professional relationship with a senior researcher who works for him who will serve as a mentor of sorts, helping to build the specific content knowledge that Brian may lack. The action steps Brian derived utilized his relative strengths while enhancing his lesser-engaged elements and moved him effectively and quickly from insight to action.Submitted by: John Elliot

Client Background

John is a successful senior manager. His personal style is poised and pleasant, characterized by high initiative and self-confidence. In general, he is highly regarded by upper management, direct reports and peers. John is extremely articulate and has no problem making himself understood in our discussion. He expresses a tendency to “shoot from the hip” on occasion in his leadership style. However, insight he gained from a recent 360º feedback indicated that his staff saw him as caring and fair. In addition, he is very goal oriented, conscientious and dependable. John describes himself as someone who is comfortable with his influence and demonstrates acute mental agility which helps him develop unique approaches to problem-solving. John indicated that he is able to meet challenges head on and is not intimidated by change and uncertainty that are constants in his work. He indicated that his very strict family upbringing was instrumental in shaping him. He has a sense of right and wrong and is very emphatic in his willingness to only choose what, in his mind, is right. He said that shades of grey are not part of how he sees his world.

John indicated that he started off his work-life as a plumber, but at the age of 34 made a decision to go to university full-time while raising a young family. He was interested in creating a better future for himself and his family that would be afforded by higher education. He indicated that his careful planning was rewarded when he earned a position with a private sector company. He eventually moved into more senior positions with increasing responsibility.

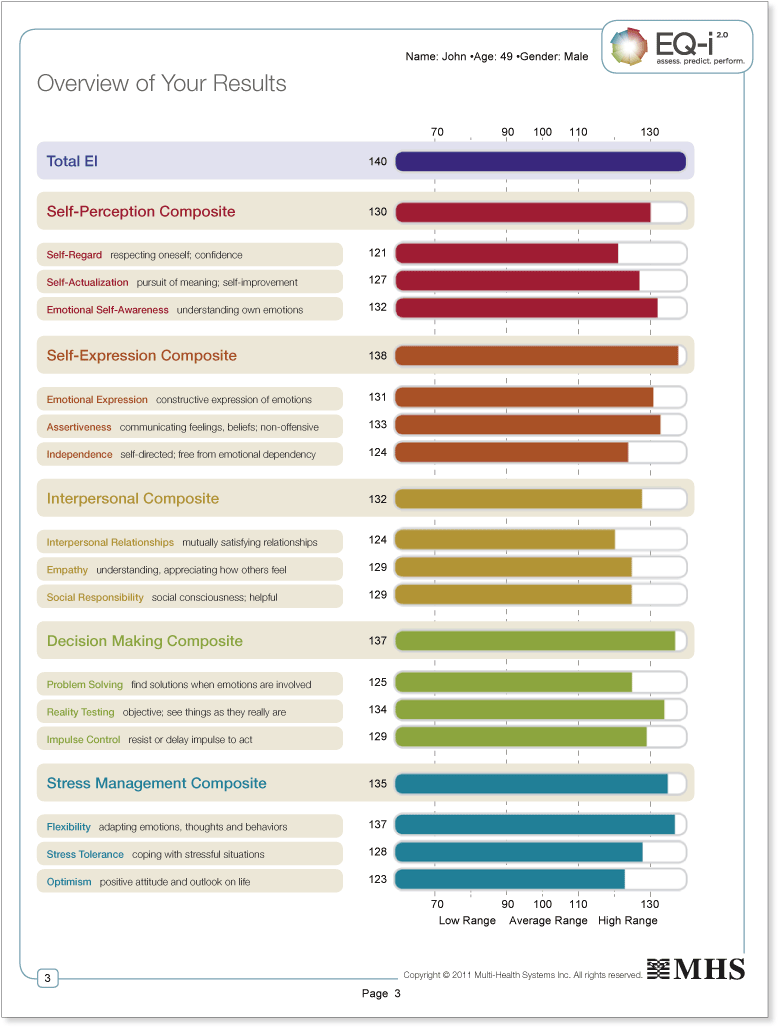

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

John’s scores on the five composite scales were all in the high range. In addition, the subscales were in the high range, indicating someone with a mastery in their emotional skills and the ability to fully understand oneself and use this information to manage emotions productively.

In reviewing John’s results, it was noted that his response style for positive impression was elevated. It was explained to John that this response style may affect the profile’s accuracy and that we needed to discuss the way he responded to the items. John explained that this is not uncommon for him and that he interprets the questions in a logical and precise way; in no way did he feel that his responses were misrepresentations about how he views himself. He used the example of high Self-Regard to clarify this point, indicating that his upbringing and the way he has lived his life has reinforced a high degree of confidence and self-respect. In addition, John indicated that his high moral code, integrity and authenticity matter very much to him. John feels that his responses truly present how he views himself.

John further indicated and recognizes that he has room to improve and that he is willing to strive towards personal improvement. He was most interested in the Interpersonal composite scores. He recognized that in his work setting his particular style does not meet the needs of all of his staff. He has been working on developing a more open approach to discussing differing points of view. He was aware of his tendency to make snap decisions (Impulse Control) and that it often isolates those he works with, leaving them to feel invalidated and misunderstood. As a result, John is committed to consciously improving his approach in this area.

Coaching Approach & Development Strategies

Even though John presented well and was adamant that he did not appraise himself higher than he thought he should, he was still willing to look at possible areas to develop. John indicated that the key to his success as a manager is the success of his staff. He wanted to use the insight gained from the EQ-i 2.0 to help him develop his interpersonal skills. He knew that he was extremely self-aware; however, he recognized that he needed to engage his staff to ensure that he was more inclusive as a manager. It was recommended that John develop a facilitative leadership style by developing a repertoire of neutral questions to promote engagement and enhanced communication. This exercise would help John to develop open and effective communication with more emphasis on listening and less of a need to expedite and solve his staff’s problems. I asked him to pay close attention to body language: his body language and that of those he interacts with. The goal is to reframe, moving away from becoming irritated and more toward becoming curious so he could engage, probe and let his staff explore how they felt. Some feedback in the past indicated his disregard for their feelings in particular situations; this change in behavior will help him address these concerns.

John is committed to providing better communication with a new perspective on his behaviors and how it impacts others. I asked John to chronicle his interactions in a journal so he could review and make adaptations to his leadership style. John agreed that journal writing would allow time for reflection/integration during the course of his day. John was asked to think of the following question when interacting with his staff, “What action can I take to ensure my staff feel listened to?"Submitted by: Kelley Marko

Client Background

Eight years ago, John left a senior executive position in a large natural-resources company and accepted a demotion to work in a Fortune 500 services organization. This life-changing decision was influenced by two factors: his desire to reduce his unreasonably long hours at work so that he could spend more time with his wife and young children, and a significant health scare that was directly related to the overwhelming stress he experienced at work. Over his eight-year tenure with his current organization, John has continued to prove his value. Now, at the age of 46, and several promotions later, John is once again occupying a senior executive position.

John’s organization has been affected by an economic downturn and this has significantly raised the level of stress and anxiety throughout the organization at being able to achieve targets and meet plans. As a result, the Executive team has been focused on short-term results and cost cutting in an attempt to satisfy the company’s shareholders. This orientation has resulted in decisions and behaviors that are fuelled by the pursuit of quick fixes that often come at the expense of engaging teamwork and leadership, even though the organization promotes the importance of these concepts through its published values.

In light of this development, John now feels the pull to return to his old and unhealthy ways of leading and managing. In an attempt to preserve his well-being and prevent his career from once again becoming derailed, John has engaged me as his executive coach to assist him in balancing the short-term needs of the company with his long-term desire to be a better leader.

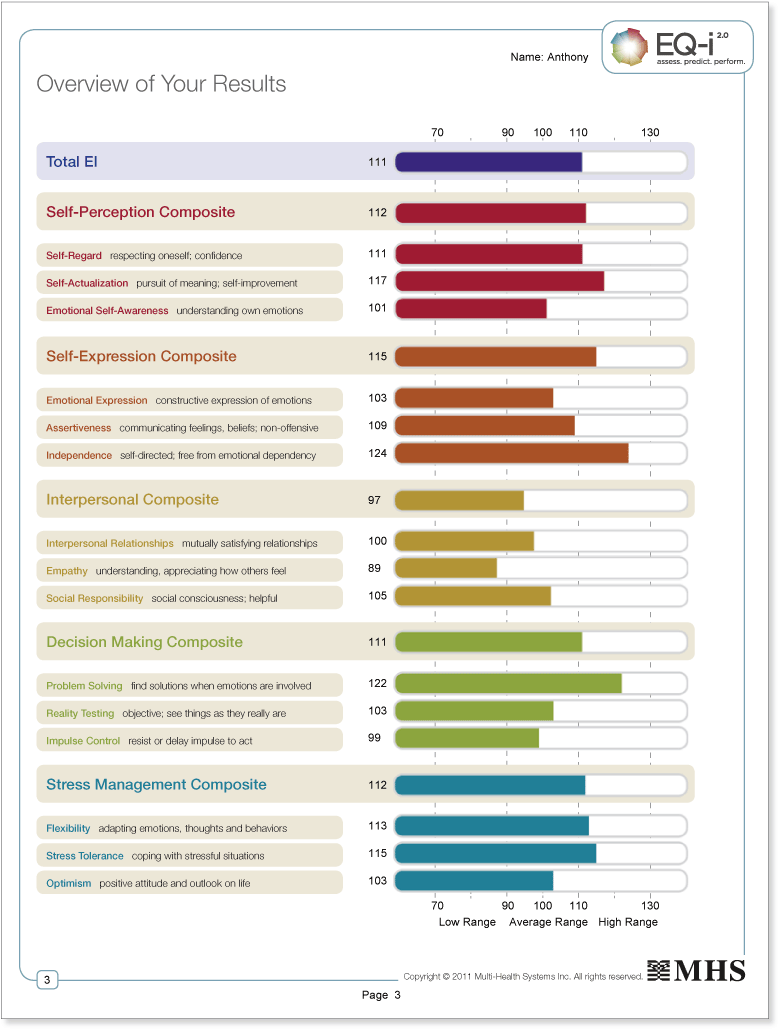

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

Coaching Approach & Development Strategies

Gaining an in-depth understanding of John’s current work and life environment through discussions and focused questions was the critical first step to moving forward with our coaching relationship. This step not only helped me better understand John’s wants and needs but also provided a foundation for better understanding his EQ-i 2.0 results in context.

An analysis of his results in conjunction with a private and confidential debrief and coaching session revealed several important revelations that provided a clear focus for our coaching relationship:

- Establishing John’s Orientation to the Difficult Work Required for Leadership Development: John’s results indicate an orientation towards deep introspection and an ability to remain accountable to his own personal development goals and commitments. First, a significantly high score on Self-Actualization confirmed John’s authentic desire to continue to develop personally and interpersonally and we linked this focus on self growth to his current desire to seek out coaching. Second, John’s high score on Self-Actualization coupled with significantly high scores on Happiness and Stress Tolerance provides evidence that he is an excellent candidate for the tough personal work involved as part of his development. These are strengths that he can rely on to help keep him on track to achieving his personal goals. Third, John’s significantly high Independence provided the foundation he needed to stand behind the belief and value he placed on executive coaching, even when other executives in the organization interpreted this type of support as a sign of weakness or an unnecessary expense in tough economic times.

- A Need to Align Intent with Behavior in His Relationships: John’s above-average Social Responsibility score is a confirmation of his personal desire to have a meaningful and sustainable impact on others and to not just focus on short-term or quick-fix perspectives that often come at the expense of people. This mindset also helped to explain some of the significant tension and dissonance that he is currently experiencing, given the decisions and behaviors of his Executive team. Despite John’s above-average score on Social Responsibility, his Interpersonal Composite was his lowest-rated theme. When we further explored the impact of John’s relatively lower scores in Empathy and Interpersonal Relationships, it revealed how his desire to be a more effective leader did not always align with his behaviors or how he is perceived by others. This disconnect was something particularly insightful for John. Given that his current business environment is characterized by high stress and anxiety, John needed to engage the skills comprising the Interpersonal Composite now more than ever. Through the use of the EQ-i 2.0, re-aligning John’s behaviors with his intentions became a developmental priority in our coaching. Although the Interpersonal Composite proved to be a primary focus, further analysis of his results revealed why maintaining balance was particularly difficult for him to do and what else he needed to focus on in our coaching.

- The Cost of Being High in Certain EQ-i Scores when Combined with Lower Impulse Control: John acknowledged that he has a tendency to take on too much and this tendency is sometimes fuelled by impulsively overusing his Independence. We explored that when John does this, he fails to develop and build relationships with others as well as he could, and in turn fails to delegate responsibilities when needed. These factors were ultimately leading to a recurring pattern of behavior from his past of working long hours and taking on an unhealthy amount of stress. Given that John’s Stress Tolerance is well above average, he often failed to recognize when he had taken on too much, both for himself and for others.

John’s relatively lower score in Impulse Control is a particularly compelling aspect of his assessment. When considered in relation to some of his highest scores, the relative imbalance proved to be particularly problematic but also insightful. John recognized that he had a hard time working with and understanding people who were not of the same skill level or mindset. For example, his significantly higher Independence, Flexibility and Problem Solving would sometimes mean that he would be several steps ahead of others and would have a harder time understanding why other people were not at the same stage he was at or why they could not keep pace. As a result, he would sometimes “leave others behind” in his desire to impulsively and quickly get things done. Understanding how his own high scores sometimes resulted in unrealistic expectations of others who may not be at his level was a key leverage point that assisted John in developing more Empathy for those he was attempting to lead. Through this process, John gained a deeper understanding of how to better manage his behaviors “in context” and that misusing his strengths can become equally problematic in certain situations.

Submitted by: Katie Ziemer

Client Background

Heather, a 33-year-old female executive assistant, completed the EQ-i 2.0 as part of an exploration exercise to guide decisions about whether or not to make a career change. In past conversations, this client has expressed excitement over several new career options in response to her discontent with her current role. She has been in an administrative role for most of her professional life but is recently questioning whether her career truly plays to her interest: directly helping people.

Prior to taking the EQ-i 2.0, the client shared that she would like to know more about where her strengths lay in order to make a more informed decision about what career change is best.

One aspiration that she discussed before completing the EQ-i 2.0, was to take a more entrepreneurial course in her career and start her own business.

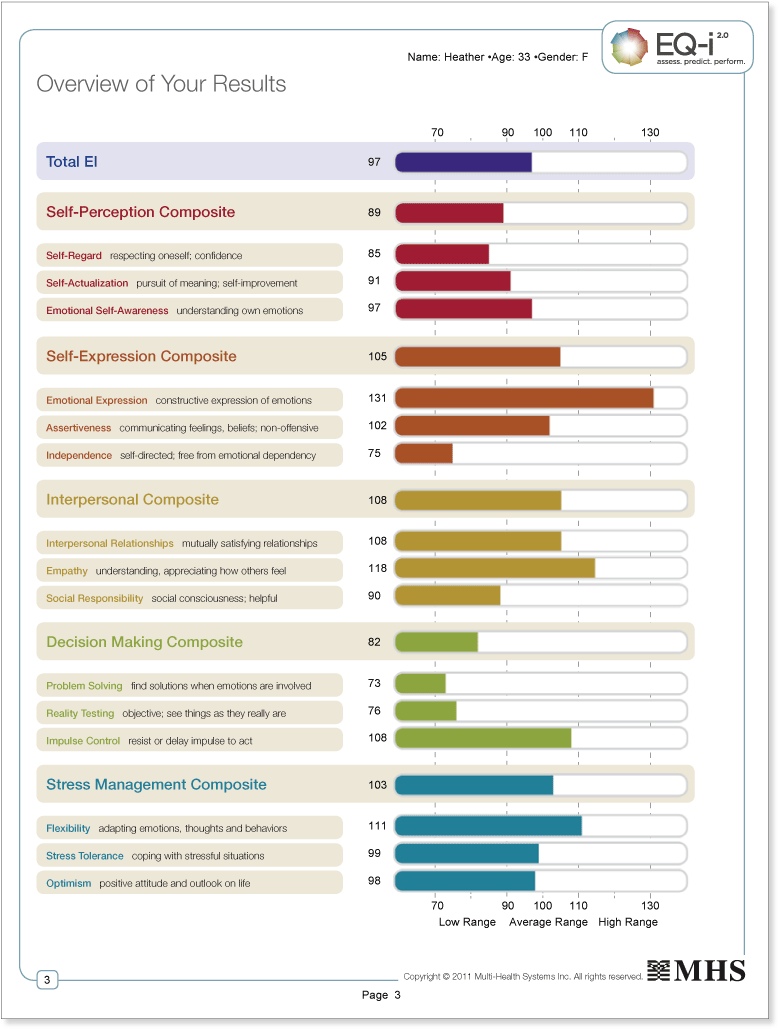

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

Heather’s profile graph reveals some interesting areas of both strength and opportunity. In a previous conversation, the client had mentioned that she feels like she copes well with the demands of her job but feels she has much more to offer, particularly when it comes to working with people. Her above average result on Empathy (118), Interpersonal Relationships (108) and Emotional Expression (131) seem to support her feelings of “wanting a job that puts her in close contact with people and allows her to truly help others.”

Reality Testing and Problem Solving are two areas that present as potential derailers should she seek her own business. Low scores in Reality Testing (76) and Problem Solving (73), coupled with both of these subscales being 30 points lower than Impulse Control (108), suggest a tendency for Heather to be delayed or paralyzed in decision making. Although generating exciting ideas may not be a problem, creating realistic plans to execute her ideas may be problematic. This concern is reinforced through her response of “occasionally” to the Reality Testing item “creating realistic plans to achieve goals.” Heather’s result in Independence, particularly her mid-range responses on items such as “I am more of a follower than leader” and “I find it hard to make decisions on my own,” suggest that while she likely has no shortage of great ideas, her ability to execute and follow through on them might be compromised, particularly if she is in a role where she alone has to react quickly to environmental demands and pressures.

Heather also presents with a Flexibility score that is higher than most other subscales on the EQ-i 2.0. As a result, Heather may appear to be less practical or pragmatic in her career decisions. Her Flexibility score coupled with low Reality Testing and Problem Solving interact in a way that may leave her susceptible to her high emotional investment/interest in a new direction without a realistic evaluation of whether she can indeed follow through with a given direction.

Coaching Approach & Development Strategies

The recommended coaching approach would be to set aside deciding on a career (which has likely spawned from her excitement to try something new without the realistic assessment of what a career change entails) and concentrate on two developmental areas:

- Gaining a clear understanding of her strengths and weaknesses

- Working through different decision making techniques and processes

Rationale

- Her response was that she only “sometimes” has a good sense of her strengths and weaknesses. There are clear subscales that could be strengths for her (i.e., Empathy [118], Emotional Expression [131], Flexibility [111] and Interpersonal Relationships [108]) where she may benefit from further understanding and realization. It may help her to examine real situations in her current role where she excelled in these areas and those outside of what the EQ-i 2.0 measures. She may need assistance in this activity because her slightly lower Self-Regard may lead her to being overly conservative in her evaluation of her capabilities.

- Building on this process, she may benefit from being introduced to some techniques for making decisions independently, including setting realistic goals and mapping out an action plan for achieving them. Although these should be small and short-term goals, they should be coupled with gathering more information about career options, and even completing additional career interest inventories. The crux of this developmental exercise would be for her to follow through on, and hold herself accountable for, completing an action plan for reaching these goals. She may need to watch her tendency to be overly expressive and that her emotions don’t overrule or overshadow an objective evaluation of a situation (i.e., extreme excitement about the idea of starting her own business versus how much commitment and follow through will be needed to get a start-up company off its feet).

Submitted by: Derek Mann

Client Background

Johann is a 39-year-old former national collegiate tennis champion, retired Association for Tennis Professional (ATP) touring professional, small-business owner, head tennis coach, husband and father, striving to achieve a work-life balance. Johann completed the EQ-i 2.0 as part of a self-development process that he has undertaken in response to the trials and tribulations he faces as a coach and professional in his community. Johann is a prominent figure in his community and is renowned for his positive demeanor, willingness to lend a helping hand, going the extra mile to help his students achieve their goals (even at the expense of his own goals), and personal and financial well-being.

Despite having a career driven by his passion, Johann is unhappy with the day-to-day operations of running his business, which he feels detracts from his passion of coaching and mentoring young athletes. However, even while coaching, Johann has recently found himself confronted with the challenges of helicopter parents and athletes with a below-average work ethic and above-average expectations. Unfortunately, Johann doesn’t challenge the status quo or voice his concerns until his back is against the wall.

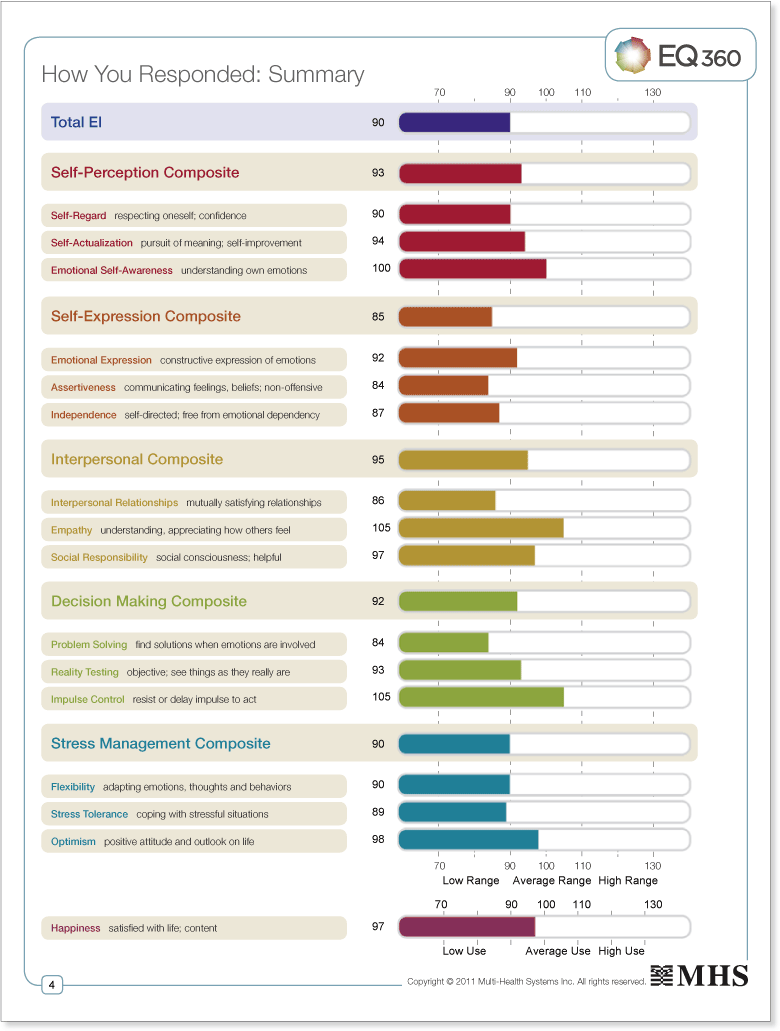

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

Overall, Johann’s total emotional intelligence score is low (90) and although this score in itself presents an opportunity for development, there are also several implications of his low Total EI score reflected at the subscale level, which impacts the process by which he addresses and copes with his day-to-day challenges. As a result, the true opportunity for Johann lies at the subscale level and the interactive effects between his relative strengths and weaknesses. Figure 11.1 highlights some of the key relationships addressed during Johann’s coaching and development.

Figure 11.1. Key Interactions Explored

| Key Relationships | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale | Score | Subscale | Score | Subscale | Score |

| IC | 105 | EM | 105 | ESA | 100 |

| FL | 90 | ESA | 100 | RT | 93 |

| ST | 89 | RT | 93 | EE | 92 |

| AS | 84 | EE | 92 | ST | 89 |

In this case, despite Johann’s Impulse Control (105) falling in the mid range, it is one of his “relative” strengths. Given his level of development, remaining resistant to temptation while not being overly reactive is a strength for Johann. Although addressing Impulse Control in isolation is a good starting point, it is equally important to take into account the interactive effects of Impulse Control. Of particular interest in this case was the interaction of Impulse Control with Flexibility, Stress Tolerance, and Assertiveness. Collectively, this combination of results indicate that Johann is not only adept at tempering his reactions, but this combination of skills might suggest that he is overly guarded, resistant to change, and in some cases, inflexible. During the feedback session, this hypothesis was explored.

Johann’s initial reaction to the probing questions during the feedback process was initially surprise, followed by thoughtful reflection. As the conversation evolved, Johann realized that although as an athlete he was open to new ideas and loved to be challenged, as a coach he feels much more vulnerable because such change implies incompetence.

Johann’s Empathy (105) is complimented by his relative strength in Emotional Self-Awareness (100). This combination of skills suggests that Johann is not only able to relate to the plight of others, he can also understand how the positive and negative emotions of others can impact his own emotional state. The difficulty for Johann lies in the combination of low Reality Testing (93), coupled with his lower Emotional Expression score (92), suggesting that Johann may misperceive the gravity of a given situation and incompletely or inaccurately express (verbally and nonverbally) how he is feeling.

While Johann possesses the ability to understand how he feels and why, it is likely that his Emotional Self-Awareness (100) coupled with his low Stress Tolerance (89) may account for why he often feels overwhelmed by the day-to-day interactions with the parents and athletes he coaches. For the most part, Johann feels stressed and is very aware of these feelings. The difficulty for Johann is that he either lacks the necessary skills or confidence in his skills to adequately cope with or modify a given situation.

Coaching Approach and Development Strategies

Collectively, Johann’s three personal strengths have shed light onto several development areas. In many cases, these development areas are directly related to the professional challenges Johann communicated prior to completing the EQ-i 2.0.

Given the relatively low scores across Johann’s profile, a combination of the model approach and narrative approach (see Giving Feedback and Coaching Fundamentals) to feedback was used to help engage Johann in the feedback process. The model approach helped to minimize the sting of the relatively low profile, while the application of the narrative approach allowed Johann to move freely through his results.

Post feedback, Johann had agreed to work on three key areas of emotional intelligence development. To provide structure to the coaching and development process, energy was directed toward the Self-Regard, Reality Testing, and Assertiveness subscales.

Self-Regard

Although Self-Regard is not among Johann’s lowest scores, it is sufficiently low to warrant attention, given that a healthy sense of self is fundamental to effective emotional and social functioning. As a result, the first step to helping Johann enhance his sense of self included conducting a Self-Regard inventory. Johann was engaged in an extensive process where he created a list of his strengths and areas that he believed needed development. Once he identified what he believed to be his areas of strength, he was encouraged to leverage these strengths whenever and wherever possible. Johann was also encouraged to meet with several friends, family members, and colleagues with whom he felt comfortable to explore what he believed to be his weaknesses.

The second step to helping Johann with his self-regard included setting specific individual goals while also setting collaborative goals with each of his athletes. By doing so, Johann was better equipped to manage both his expectations and the expectations of his athletes. In many cases, Johann developed specific, measurable, and action-oriented goals, and when necessary he further broke down his goals into smaller mini-goals.

Reality Testing

Johann is perceptive, but he has the tendency to misinterpret cues, which has often resulted in Johann feeling stressed, overwhelmed, and frustrated. Johann needed to better understand how to validate the information he was attuned to. Johann’s responsibility was to identify three specific people from the groups he outlined above and that he felt truly comfortable with. During regular interactions, Johann was to describe the context of a given situation, what he perceived to be happening, and the emotional tone and implications of the situation. This process exposed Johann to the gaps he was experiencing in many of his interactions.

Assertiveness

During the coaching and development process it became very clear that Johann’s discomfort with voicing his opinion and standing behind his decisions, or in many cases remaining passive in the face of a disagreement with a parent or athlete, was deep rooted in his low self-regard. Coupled with the above mentioned process for helping Johann improve his sense of self, Johann worked on expressing a variety of thoughts, ideas, and feelings while learning that being expressive is perfectly acceptable, provided that the delivery is non-offensive and non-destructive. In fact, learning to be more assertive and expressive was crucial to his success.

Placing emphasis on Self-Regard, Reality Testing, and Assertiveness during the initial coaching period provided the necessary skills to help Johann begin to realize the opportunities that lay ahead. It also helped provide the foundation for future coaching to enhance the coping skills that Johann needs to be truly effective and happy with his day-to-day responsibilities.Submitted by: Deena Logan, Derek Mann, Katie Ziemer

Client Background

A large U.S. based pharmaceutical company was interested in identifying their sales representatives’ strengths and development opportunities. Despite having a well-developed and established competency model, this organization was particularly interested in the added insight made available by completing the EQ-i 2.0.

A sample of 137 sales representatives agreed to complete the EQ-i 2.0. Sales representatives were also evaluated by their respective manager or supervisor on each of seven competencies: Market and Therapeutic Knowledge, Selling the Portfolio, Building and Sustaining Valued Partnerships, Analysing, Prioritizing and Planning, Executing, Evaluating and Adjusting, EQ-Related Behaviors, and Overall Performance. Sales representatives were rated on their performance relative to the other sales representatives in their unit, on a 5-point scale from “weak” to “best.”

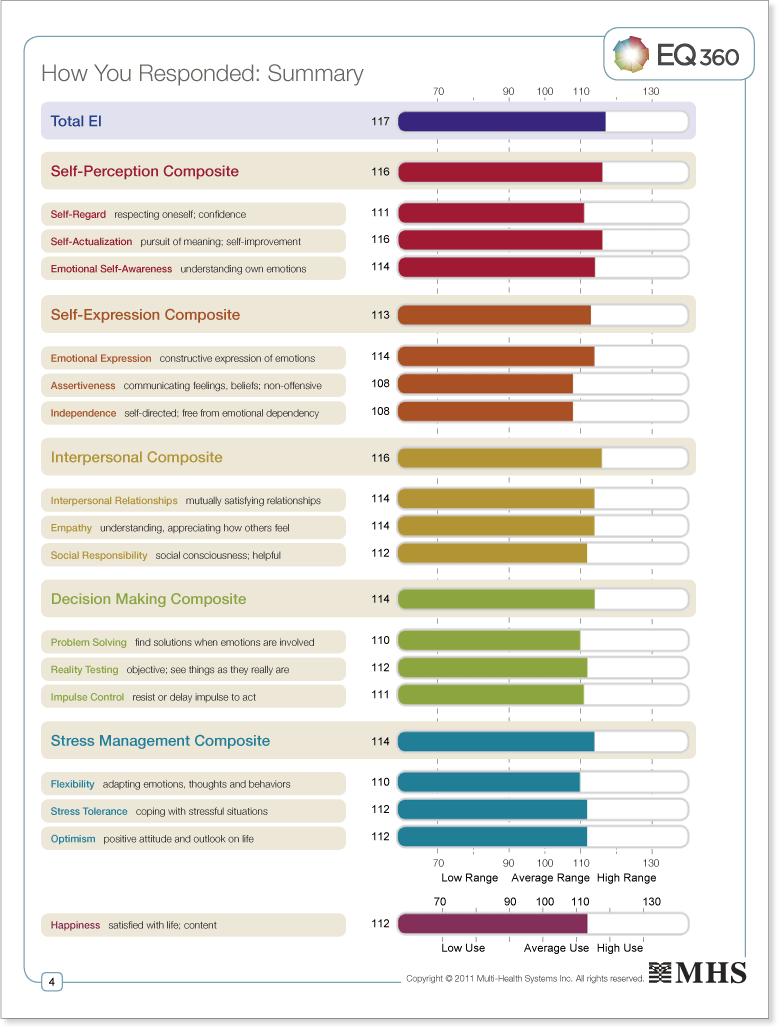

Summary of EQ-i 2.0 Results

Collectively, the sales representatives have a Total EI score of 117, suggesting, on average, a high level of emotional and social functioning across team members. The same result holds true across the five composite and subscales with average scores ranging from 108 (Independence) to 116 (Self-Actualization). Considering that only 25% of the EQ-i 2.0 normative population score above 110, these scores suggest that this group is equipped with effective emotional and social functioning skills. Specifically, the Self-Perception (116) composite and the Interpersonal (116) composite results indicate an inner strength, confidence, and personal drive while maintaining the ability to develop and maintain relationships based on trust and compassion; two attributes that are integral to sales success.

However, when considering the collective results of individuals, there is a tendency for top and bottom performers to washout in the averaging process. As a result, to truly understand the impact that emotional intelligence has on the performance rating of these sales representatives, it is helpful to divide the sample into groups of performers based on performance ratings (in this case provided by managers and supervisors). For each of the competency areas outlined above, the sample was divided into thirds in order to compare the top and bottom performers on the EQ-i 2.0 scales. A number of significant differences in EQ-i 2.0 scores were observed between groups, demonstrating a relationship between emotional intelligence and performance. Group means and Cohen’s d measures of effect size are described below for each competency.

With regard to Market and Therapeutic Knowledge, the top performance group scored higher than the bottom performance group on Impulse Control (M = 114.75 vs. M = 108.73, d = .47), as well as on the Decision Making composite (M = 117.14 vs. M = 112.26, d = .43).

For Analyzing, Prioritizing, and Planning, the top performance group showed lower scores compared to the bottom performance group on a number of EQ-i scales, including Emotional Self-Awareness (M = 110.02 vs. M = 116.34, d = .48), Emotional Expression (M = 112.54 vs. M = 117.90, d = .49), Interpersonal Relationships (M = 111.61 vs. M = 115.56, d = .49), Empathy (M = 111.74 vs. M = 117.64, d = .56), and the Interpersonal composite (M = 113.23 vs. M = 118.74, d = .58).

For EQ-related behaviors, the top performance group scored higher than the bottom performance group on Impulse Control (M = 114.80 vs. M = 106.78, d = .56), the Decision Making composite (M = 116.92 vs. M = 111.49, d = .41), and the Stress Management composite (M = 116.20 vs. M = 111.63, d = .47).

Concerning overall performance, the top performance group scored higher than the bottom performance group on Impulse Control (M = 114.43 vs. M = 108.55, d = .45).

Most notable among these results is the relationship between Impulse Control and the areas of Demonstrating Market and Therapeutic Knowledge, EI-related behaviors, and Overall Performance. Salespeople are hungry for that next opportunity, but individuals with strong impulse control are better able to resist the urge to make quick promises or rush into providing a solution for a customer when their needs aren’t yet fully understood. Those with high impulse control tend to ask questions first rather than overreacting to negative emotions or relying on assumptions.

Also notable is the inverse relationship between Analyzing, Prioritizing, and Planning and a number of EQ-i 2.0 scales in the Self-Perception, Self-Expression, and Interpersonal areas. This pattern is not uncommon with sales-type roles. While these skills are of course necessary and can be advantageous for someone in a sales position, an overemphasis on such behaviors can have certain drawbacks. Becoming too heavily focused on emotions and relationship maintenance can cause one to lose sight of the task at hand, and other job requirements can suffer as a result. Being overly empathic can make it difficult to remain objective and prioritize tasks appropriately when strong emotions are involved, and cause one to avoid making tough decisions or dealing proactively with important client management issues. Furthermore, too much self-reflection can lead to feelings of insecurity in one’s abilities, and expressing such feelings too freely might make one appear incompetent, with the result that others may lose confidence in that person as a sales professional.

No significant differences in EQ-i 2.0 scores were observed on three of the scales, namely Selling the Portfolio, Building and Sustaining Valued Partnerships, and Executing, Evaluating, and Adjusting.

The fact that the top and bottom performers did not differ on the remaining EQ-i 2.0 scales is not to say that emotional intelligence is unimportant to success in these areas. Rather, this may be due to the limited variability in EQ-i 2.0 scores for this sample. As a whole, this group of sales representatives scored well above average across all emotional intelligence areas as measured by the EQ-i 2.0, and this is the case for both the top and bottom performance groups. For the results described above, the lower EQ-i 2.0 scores observed for the top or bottom performance group (depending on the scale in question) were not actually “low” scores, but were in the upper end of the mid range, or in the high range, compared to the general population.John Elliott

Senior Course Designer Trainer & Facilitator

John Elliott is a graduate of both York University and the University of Toronto. He holds degrees in Psychology. In addition to his academic credentials, John has extensive skill as a coach and is certified as an EQ Coach and facilitator. His experience in leading organizations and managers through change has been part of his repertoire for over 20 years. He has provided his services to a wide cross-section of clients across a variety of sectors. He has been recognized as an effective presenter who is capable of engaging his audience in interactive and meaningful training. In the past, he has had a robust career in a management and life-skills coaching practice, helping individuals to strive towards their goals.

Currently, he is researching a book on integrating employee development within the context of knowledge management. He is also active in teaching at the post-secondary level and has acted as a mentor for future leaders in organizations. John’s insights in helping organizations and individuals meet goals make him a sought after coach and speaker. John translated his expert knowledge of individual and managerial competencies into training that resulted in better and more effective individual performance and team work. For organizations, his insights and training led to both higher performance and increased productivity.

John is a leading practitioner in the field of Emotional Intelligence. John has provided many leaders with an understanding of EQ skill that have helped them accelerate their career prospects. In the past few years John has been supporting leadership and training programs within the OPS. He has designed, developed and delivered numerous courses that specifically support OPS strategic initiatives in the development and retention of talent.

Since 1989, he has spoken to over 1,500 audiences, many of them repeat engagements. His clientele includes Fortune 100 companies, government at all three levels in Canada, and many international corporations. He works in a variety of contexts, including corporate leaders and government officials, representing a remarkably diverse cross-section of the economy. John is much sought after as a speaker, curriculum developer, trainer and executive coach. He has presented keynote speeches, workshops, and seminars all across Canada. His high-quality, high-energy programs are both well-researched and delivered. John’s courses are delivered in a down-to-earth style that makes his training a memorable and satisfying experience.

Kelley Marko, MBA, MA

Consultant, Executive Coach and Learning Facilitator

Kelley is president of Marko Consulting Services Inc., a leading Canadian firm working with organizations worldwide in developing high-performance leaders and enabling sustainable and meaningful change. In all his work, Kelley’s ultimate focus is to move individuals and organizations to strategy and informed action that impacts the bottom line.

Kelley is also a professional executive coach and certified adult educator. He is a master trainer and coach of emotional intelligence (EQ) and has worked with hundreds of leaders across diverse industries to improve their competencies. Kelley holds an MBA from York University and an MA in Leadership and Learning from Royal Roads University. In addition to leading his own professional practice, Kelley is a seminar leader, and customized in-house program facilitator for the Schulich Executive Education Centre at York University, Toronto, Canada.

His background incorporates front-line through senior leadership positions in industry and professional management consulting with PriceWaterhouseCoopers and in partnership with McKinsey in the area of organization and change strategy. Based in the Toronto, Canada area, Kelley has worked with organizations around the globe including Bell Canada, Toyota, IBM, American Express, Atomic Energy of Canada, Laidlaw Carriers, MOEN, YellowPages Group, and Outward Bound.

Hile Rutledge, MSOD

CEO, OD Consultant, and Author

CEO and Owner of OKA (Otto Kroeger Associates), Hile is author of the EQ-i®, MBTI® Introduction, the Four Temperaments Workbooks and the co-author of the revised Type Talk At Work, Generations: Bridging the Gap with Type and Reversing Forward. Hile Rutledge is an experienced organization development consultant, trainer and public speaker with a background in management, sales, adult education and leadership development. Hile’s primary area of expertise is the use of the Myers-Briggs Type Indicatorâ and the EQ-i assessments as self-management, leadership and communication tools. Hile has done extensive work with both public and private sector clients whose needs range from team building, communications and feedback training, conflict management, strategic planning and other large group events and skills-based workshops.

During his career, Hile has found success in archaeology, public relations, sales management, career counselling and independent organization development consulting. Hile has a BA in Humanities from Hampden-Sydney College and a Master of Science in Organization Development from the American University (AU/NTL). Hile resides with his wife and two sons in Falls Church, Virginia.

Marcia Huges, JD

Consultant, Master Trainer, and Author

Marcia Hughes is President & CEO of Collaborative Growth, and serves as a strategic communications partner for organizations. Marcia and her team offer team building, keynotes, workshops, and leadership and employee development to provide organizations with strategic behavior alignment by bringing their values, intentions and behaviors into sync. As master trainers and facilitators, Collaborative Growth’s mission is to provide consulting which results in lasting behavioral change. As an international leader in EI, Marcia is a member of the EI Consortium.

Marcia and her partner, James Terrell, are authors of The Team Emotional & Social Intelligence Survey® (TESI®), an online team assessment. She is co-author of The Handbook for Developing Emotional Intelligence, A Facilitator’s Guide to Team Emotional and Social Intelligence, A Coach’s Guide to Emotional Intelligence, The Emotionally Intelligent Team, and Emotional Intelligence in Action and author of Life’s 2% Solution. Marcia practiced law for over 20 years, operating her own successful law firm, which focused on complex public policy matters. Before entering private practice, Ms. Hughes worked with governmental and public interest organizations. She served as a special assistant to the Executive Director of the Department of Public Health and the Environment and as an Assistant Attorney General. She clerked on the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals for the Honorable William E. Doyle and served with the Environmental Protection Agency in Washington, D.C. Clients include the World Bank, Medtronic, American Express, Toronto School Board, federal, state and local governments, corporations, non-profits and foundations.

Dana Ackley, Ph.D.

CEO, Executive Coach, and Author

Dana C. Ackley, Ph.D., is CEO of EQ Leader, Inc., a consulting and executive coaching firm that helps successful leaders prepare for their next level of achievement. He earned his Ph.D. in psychology in 1973. Since that time he has worked with leaders from a variety of organizations, including Fortune 500 companies, the Federal Government, healthcare systems, law enforcement, and local government. He and his colleagues use psychological principles to build leadership skills that become deeply anchored in the individual they coach.

His EQ Leader Program (MHS, 2006) is a comprehensive, step-by-step approach to executive EQ skill development. It includes workshops, EQ assessment, development planning, work-based exercises and executive coaching to move participants from conceptual understanding to lasting behavior change. The EQ Leader Program is used by coaches and organizations around the world. Training in the program is available through EQ Leader, Inc.

Derek Mann, Ph.D.

Manager R&D, Consultant, and Author

Derek T.Y. Mann, Ph.D., is a performance enhancement consultant and co-founder of the Performance Psychology Group, LLC (PPG), an organization responsible for providing coaching services to athletes and corporate executives across North America.

Derek has spent several years investigating the impact of emotion on human performance with elite populations which has been published in several leading professional and academic publications. Most recently he has co-authored the Emotional Intelligence Skills Assessment. Given his expertise in this domain, Derek has also served as a contributing editor to several leading academic and professional journals.

Derek is currently a Manager, Research and Development at Multi-Health Systems Inc., where he has contributed to the growth and accessibility of emotional intelligence through assessment, training and development, and professional presentations throughout North America.

Katie Ziemer, MOrgPsych

Senior Research Associate, 360° Specialist

Katie Ziemer is a Senior Research Associate with MHS specializing in the development of corporate assessments and, most recently, the revision of the EQ-i 2.0. With a background in organizational development, performance measurement, training and 360° feedback delivery and design, Katie’s focus has always been on blending practices grounded in psychological science into individual and organizational measurement strategies.

Katie has been an external consultant to both private and public organizations across Canada and Australia. She received her BSc (Hons) from St. Mary's University in Halifax and her Master's in Organizational Psychology from Curtin University in Australia. Her education and industry experience is currently being applied to the assessment and sustained development of emotional intelligence.

Brett Richards, MA

President, Global Consultant

Brett is the founder and President of Connective Intelligence Inc., a global consulting firm that offers business-based solutions to improve the current performance and future potential of organizations. Connective Intelligence specializes in mapping and developing thinking and emotional capabilities to increase individual, team and organizational performance. In addition, Brett is an industry practitioner instructor at the Schulich Executive Education Centre.

With a long time interest and academic training in emotional intelligence, he is also a Master Trainer and Coach with the EQ-i® (emotional quotient inventory) and is the developer of Emotional Power®, a practical business-based model used to apply the concepts of emotional intelligence in the workplace.

Deena Logan, MA

Psychometrician, EI Specialist

Deena is a Psychometrician in Research and Development at Multi-Health Systems Inc., working primarily with emotional intelligence assessments. Areas of focus include applied work on the predictive ability of EI in relation to job performance, and international adaptations of MHS EI tools.