The EQ-i 2.0 Framework

Since the seminal work of Bar-On (1997, 2004), interest in emotional intelligence has continued to blossom. In response to the vast research that has emerged over the years, the operational definition of emotional intelligence has evolved, affecting the conceptual model of emotional intelligence and driving the need to reconsider empirically the factor structure of the EQ-i® (Bar-On, 1997). The final form of the EQ-i® 2.0 consists of 133 items, representing 15 subscales (with 7 to 9 items per subscale), a Well-Being Indicator and 3 Validity Indicators, teamed with a corresponding 360 degree assessment that is designed to complement the EQ-i 2.0.

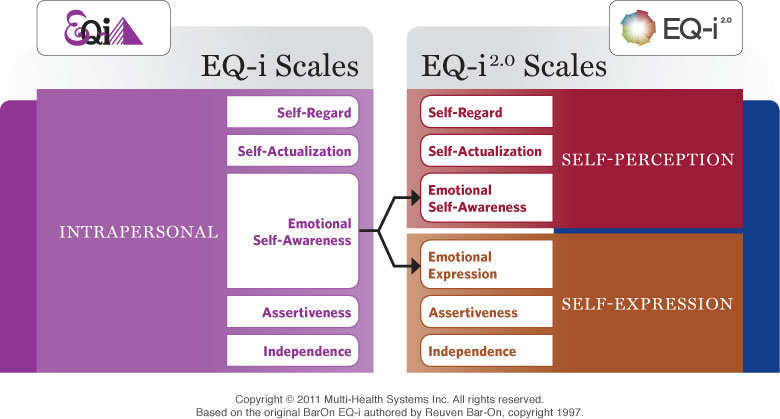

Although based on the original factor structure of the EQ-i (Bar-On, 1997), the EQ-i 2.0 and EQ 360® 2.0 are the products of several model changes that are deemed practically, empirically, and theoretically sound. A side-by-side comparison of the EQ-i factor structure to that of the EQ-i 2.0 can be seen in Figure 3.1. The process used to arrive at the conceptual changes has involved many steps, including item analyses, item development, data collection and analysis, and expert reviews. A detailed description of the Stages of Development can be found in EQ-i 2.0 Stages of Development and statistical support for the model changes can be found in Standardization, Reliability, and Validity.

It is the goal of this and the next section to highlight the major changes to the model of emotional intelligence, including changes to the operational definition of emotional intelligence and the realignment of the Intrapersonal, Adaptability, Stress Management, and General Mood Composite scales, while addressing modifications to their underlying subscales.

The realignment of the composite scales and subscales yields a model of emotional intelligence that is even more intuitive than its predecessor. The total EI score is considered a snapshot of one’s overall emotional intelligence and potential for effective emotional and social functioning. The EI composite and subscales provide an opportunity to look deeper into the underlying facets of emotional intelligence that drive behavior. The following structural and alignment changes of the EQ-i have resulted in a model better equipped to serve this purpose.

Figure 3.1. A comparison of the EQ-i and the EQ-i 2.0

Intrapersonal Composite

The Intrapersonal Composite scale of the EQ-i was initially comprised of two related but functionally unique content areas: self-awareness and self-expression. The rich information provided by the combination of the Self-Regard, Self-Actualization, and Emotional Self-Awareness subscales spawned insight into how a given individual perceived him or herself. While the combination of Assertiveness and Independence reflected how one presented one’s internal self to the external world, these areas did not directly assess the overt expression of emotions. Previously, the Emotional Self-Awareness subscale captured how one not only perceived, but also expressed, oneself.

Upon reflection, consultation, and further data analysis, a logical divide became evident: split the Intrapersonal Composite scale to more specifically and deliberately address how one perceives oneself, and complement that composite scale with a new composite scale capturing how this internal perception is expressed. As a result, the Intrapersonal Composite scale was divided and the Self-Perception and Self-Expression Composite scales were born.

To fully account for this division, the content of the Emotional Self-Awareness subscale now needed to conform to the new factor structure. The items pertaining to self-awareness were retained and now reside in the Emotional Self-Awareness subscale of the Self-Perception Composite. The self-expression items were also retained and expanded to better address how one expresses oneself, inspiring the addition of the Emotional Expression subscale. The end result captures the essence of emotional perception and emotional expression by way of two unique but related composite scales, each containing three subscales (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. The realignment of the Intrapersonal Composite Scale

Interpersonal Composite

The Interpersonal Composite scale of the EQ-i was designed to address one’s ability to develop and maintain mutually satisfying relationships; remain comfortable and competent while meeting and relating to others; and be a contributing and effective member of one’s social group. The inclusion of the Interpersonal Relationships, Empathy, and Social Responsibility Subscales proved to be a powerful component of emotional intelligence. Although minor changes to the items were made, this composite scale was left intact.

Adaptability and Stress Management Composite

Two defining aspects of emotional intelligence include how well we cope with our daily demands and pressures, and how effectively we use emotional information to optimize our decision making process.

The Impulse Control and Stress Tolerance subscales combined to provide insight into how well one could tolerate stress without experiencing significant setbacks, falling apart, or even losing control. Although beneficial, the Stress Management Composite did not include the mechanisms that could help an individual buffer stress or otherwise cope with arguably the greatest source of stress: change. Upon reflection and data analysis it seemed that in order to better address the needs of a Stress Management Scale, a natural psychological buffer was necessary, as was the need to address one’s capacity to cope with change. As a result, the Stress Management Composite was restructured to include Optimism (a natural factor for enhancing one’s ability to tolerate, and remain resilient in the face of, stress), Flexibility (ability to adapt to change), and Stress Tolerance (ability to cope with and manage stress).

It was also recognized that well established emotional intelligence includes the ability to use emotional information to optimize decision making, and that the Adaptability Composite could be restructured to cover this key element and provide enhanced utility to the end user. The Decision Making Composite was established and consists of the three subscales of Problem Solving, Reality Testing, and Impulse Control. Together the three subscales capture the process one is likely to use when making decisions. The application of emotional information (Problem Solving), while remaining objective (Reality Testing), paired with the ability to delay immediate gratification (Impulse Control) when necessary, provides the foundation for making effective decisions.

The realignment and restructuring of the Adaptability and Stress Management Composite scales (Figure 3.3) has resulted in the formation of the Decision Making Composite, which is intuitive, easy to coach, conceptually sound, and addresses a key element of functioning. As well, there is a more structurally sound and practical Stress Management Composite. The notion of Adaptability is still deemed important but, defined broadly, the construct of adaptability runs across the many facets of emotional intelligence.

Figure 3.3. Realignment and restructuring of the Adaptability and Stress Management Composite Scales

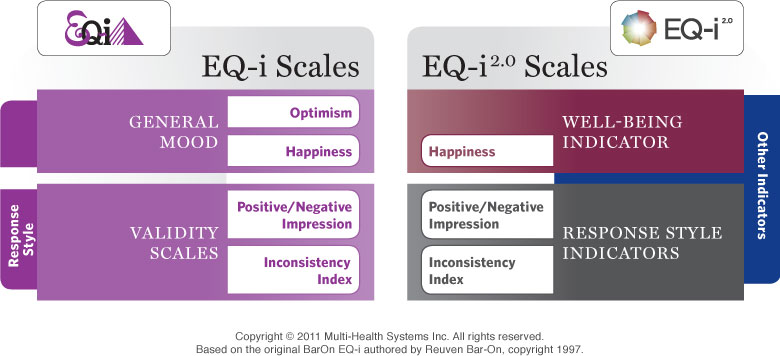

General Mood

The General Mood Composite has long been considered a barometer of one’s overall emotional intelligence. After all, emotional intelligence is an indicator of social and emotional effectiveness and well-being. However, the General Mood Composite - made up of Optimism and Happiness – can be considered a product of one’s emotional intelligence. Although optimism and its associated behaviors can be taught, acquired, and developed, happiness on the other hand is a direct by-product of many other behaviors, beliefs, and attitudes. As a result, it was determined that Optimism served a greater function in the Stress Management Composite, leaving Happiness as an isolated factor. Given the unique information that the Happiness subscale brings to the EQ-i, it needed to be retained.

In recent years an abundance of research into happiness has appeared in academic and mainstream chronicles, with a common message: “Happiness is essential to well-being and quality of life, but you don’t just become happy.” Happiness is an attitude and a by-product of other psychological skills that one has at his or her disposal (Davidson & Lutz, 2008; Flora, 2009; Seligman, 2002). Happiness can be considered a consequence of emotional intelligence and, as a result, has been retained as a well-being indicator: a measure of one’s feelings of satisfaction and contentment.

Figure 3.4. Realignment and restructuring of the General Mood Composite Scale

The heart and soul of the EQ-i 2.0 resides in its conceptual framework, a framework that is based on the original EQ-i model (Bar-On, 1997) and continues to provide unique access into one’s emotional and social functioning and well-being. This section is designed to provide a thorough understanding of the conceptual view of emotional intelligence as measured by the EQ-i 2.0, including the operational definitions of the many components being measured. Mastering an understanding of the conceptual framework of the EQ-i 2.0 is the first step in the successful application of the tool and provides the basis for evaluating and interpreting results.

Not unlike the need to update and improve the EQ-i itself, it is necessary to consider the overarching framework that guides these changes. Recent advances in both the research and practice of emotional intelligence have resulted in a deeper understanding of what emotional intelligence is, what it looks like, how we talk about it, and ultimately how it can be captured, resulting in a need to refine our working definition. In response to these advancements Emotional Intelligence is defined as

…a set of emotional and social skills that influence the way we perceive and express ourselves, develop and maintain social relationships, cope with challenges, and use emotional information in an effective and meaningful way.

Emotional intelligence (EI) —as defined here and applied in the Emotional Quotient Inventory (EQ-i 2.0) —reflects one’s overall well-being and ability to succeed in life. The richness of this operational definition is reflected in one’s level of functioning at the composite level and further enhanced by an understanding of the interconnectedness of the 15 different factors that comprise the EQ-i 2.0.

It is of paramount importance that the coach, consultant, counselor, or practitioner understands that, although emotional intelligence is a significant predictor of personal and professional success and well-being, emotional intelligence does not operate in a vacuum. Emotional intelligence combines with other important attributes, such as genetic predispositions, intellectual capacity, trained skills, motivation, and environmental factors, all of which together impact one’s propensity for success and well-being. This approach is in agreement with the “interaction position” adopted by Bem and Allen (1974), which stressed that assessment must seriously attend to personal factors and environmental situations to predict behavior. Epstein (1979) further emphasized this position, underscoring that the question of whether a given situation or the person involved in it is more important is meaningless, because behavior is always the complex interaction between the person and the situation. As a result, it is moot to talk about characteristics of an individual’s behavior without specifying and gaining an understanding of the situation in which the behavior occurs.

The framework from which the EQ-i 2.0 is derived identifies 15 separate but related factors that provide structure for the meaningful interpretation of the interaction between a person and his or her environment. In essence, the 1, 5, 15, factor model of the EQ-i 2.0 relates to an individual’s potential for success and well-being, and is not a direct measure of it. As a result, a thorough understanding of the EQ-i 2.0 framework provides invaluable insight into a person’s potential: it sheds light onto the depth and breadth of his or her processes for dealing with thoughts, feelings, and emotions, and for interacting with the outside world.

The following section expands on the operational definition of EI that provides the foundation for the EQ-i 2.0, including a description of the five composite factors and their respective subscales. The composite scales are designed to provide a ’macro’ perspective on one’s level of emotional and social functioning by giving insight into the individual’s perception of his or her inner self; the outward expression of this perception; and his or her ability to establish and maintain relationships, apply emotional information, and cope with and manage stress. Each composite scale is comprised of a subset of skills that provide the functional utility of the EQ-i 2.0 (Figure 3.5).

Figure 3.5. Factor Structure of the EQ-i 2.0

The 15 subscales provide the EQ-i 2.0 with the functional utility that coaches, counselors, HR professionals, and corporate executives have come to expect. Emotional skills and emotional intelligence develop over time, with experience, and in direct relation to deliberate practice. Each of the subscales of the EQ-i 2.0 sheds light onto the many emotional facets related to well-being and performance; as a result, both well-being and performance can be enhanced when an individual learns how to leverage his or her natural strengths while gaining a greater understanding of — and developing the skills to evolve — the areas of emotional intelligence that are underutilized (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6. EQ-i 2.0 Model of Emotional Intelligence

Self-Perception

This facet of emotional intelligence addresses the inner self. The subscales include Self-Regard, Self-Actualization, and Emotional Self-Awareness, which together are designed to assess feelings of inner strength and confidence, persistence in the pursuit of personally relevant and meaningful goals, and an understanding of what, when, why, and how different emotions impact thoughts and actions.

This facet of emotional intelligence addresses the inner self. The subscales include Self-Regard, Self-Actualization, and Emotional Self-Awareness, which together are designed to assess feelings of inner strength and confidence, persistence in the pursuit of personally relevant and meaningful goals, and an understanding of what, when, why, and how different emotions impact thoughts and actions.

Self-Regard is respecting oneself while understanding and accepting one’s strengths and weaknesses. Self-Regard is often associated with feelings of inner strength and self-confidence. Self-acceptance is the ability to accept one’s perceived positive and negative aspects as well as one’s limitations and possibilities. This component of emotional intelligence is associated with general feelings of security, inner strength, self-assuredness, self-confidence, and self-adequacy. Feeling sure of oneself is dependent upon self-respect and self-esteem, which are based on a well developed sense of identity. A person with a well-developed self-regard feels fulfilled and satisfied with him or herself. At the opposite end of the continuum are feelings of personal inadequacy and inferiority.

Self-Actualization is the willingness to persistently try to improve oneself and engage in the pursuit of personally relevant and meaningful objectives that lead to a rich and enjoyable life. Striving to actualize one’s potential involves engaging in enjoyable and significant activities and making a lifelong and enthusiastic commitment to long-term goals. Self-actualization is an ongoing, dynamic process of striving toward maximum development of one’s abilities, capacities, and talents. This component of emotional intelligence is associated with persistently trying to do one’s best and improve oneself in general. Self-actualization is associated with feelings of self-satisfaction.

Emotional Self-Awareness includes recognizing and understanding one’s own emotions. It involves the ability to differentiate between subtleties in these emotions, while being aware of their causes and the impact they have on the thoughts and actions of oneself and others. At the core of emotional self-awareness is the ability to know what one is feeling and why, while being able to recognize and understand the source of those feelings.

Self-Expression

The Self-Expression Composite scale is an extension of Self-Perception and addresses the outward expression or the action component of one’s internal perception. This facet of emotional intelligence is comprised of Emotional Expression, Assertiveness, and Independence. It assesses one’s propensity to remain self-directed and openly expressive of thoughts and feelings, while communicating these feelings in constructive and socially acceptable ways.

The Self-Expression Composite scale is an extension of Self-Perception and addresses the outward expression or the action component of one’s internal perception. This facet of emotional intelligence is comprised of Emotional Expression, Assertiveness, and Independence. It assesses one’s propensity to remain self-directed and openly expressive of thoughts and feelings, while communicating these feelings in constructive and socially acceptable ways.

Emotional Expression is openly expressing one’s feelings verbally and non-verbally. Emotional expression extends beyond the simple overt expression of one’s feelings, to include the communication of those feelings in a manner that can be understood and experienced by the recipient.

Assertiveness involves communicating feelings, beliefs, and thoughts openly, and defending personal rights and values in a socially acceptable, non-offensive, and non-destructive manner. Assertiveness is a complex and essential component of emotional intelligence that transcends one’s ability to express emotion. Assertiveness includes the expression of feelings, but further encompasses one’s ability to openly express thoughts, beliefs, and ideas, even in the face of adversity, and to defend and stand up for one’s personal rights.

Independence is the ability to be self-directed and free from emotional dependency on others. Decision making, planning, and daily tasks are completed autonomously. Independent people are self-reliant in planning and making important decisions; however, highly independent individuals may seek and consider the opinions of others before making the best decision. Seeking consultation or advice and gathering information are not signs of dependency. Independence is the ability to function autonomously without protection and support: independent people avoid clinging to others to satisfy their emotional needs.

Interpersonal

The Interpersonal Composite scale includes Interpersonal Relationships, Empathy, and Social Responsibility. This facet of emotional intelligence measures one’s ability to develop and maintain relationships based on trust and compassion; articulate an understanding of another’s perspective; and act responsibly while showing concern for others, a team or a greater community/organization.

The Interpersonal Composite scale includes Interpersonal Relationships, Empathy, and Social Responsibility. This facet of emotional intelligence measures one’s ability to develop and maintain relationships based on trust and compassion; articulate an understanding of another’s perspective; and act responsibly while showing concern for others, a team or a greater community/organization.

Interpersonal Relationships refers to the skill of developing and maintaining mutually satisfying relationships that are characterized by trust and compassion. Mutually satisfying relationships include social interchanges that are potentially meaningful, rewarding, and enjoyable. Among positive interpersonal relationship skills are the ability to connect with others by remaining open and by a willingness to both give and receive affection and intimacy; and the ability to remain at ease and comfortable in social situations. This emotional skill requires sensitivity toward others, the desire to establish meaningful relationships, and the ability to feel satisfied with relationships.

Empathy is recognizing, understanding, and appreciating how other people feel. Empathy involves being able to articulate your understanding of another’s perspective and behaving in a way that respects others’ feelings. At the core of empathic behavior is being able to perceive and appreciate what, how, and why people feel the way they do - being able to emotionally “read” other people - while demonstrating an interest in and concern for others.

Social Responsibility is willingly contributing to society, to one’s social groups, and generally to the welfare of others. Social Responsibility involves acting responsibly, having social consciousness, and showing concern for the greater community.

Decision Making

The Decision Making Composite scale addresses the ways in which one uses emotional information. This facet of emotional intelligence includes Problem Solving, Reality Testing, and Impulse Control. Collectively, this composite scale reveals how well one understands the impact emotions have on decision making, including the ability to resist or delay impulses and remain objective in order to avoid rash behaviors and ineffective attempts at problem solving.

The Decision Making Composite scale addresses the ways in which one uses emotional information. This facet of emotional intelligence includes Problem Solving, Reality Testing, and Impulse Control. Collectively, this composite scale reveals how well one understands the impact emotions have on decision making, including the ability to resist or delay impulses and remain objective in order to avoid rash behaviors and ineffective attempts at problem solving.

Problem Solving is the ability to find solutions to problems in situations where emotions are involved. Problem solving includes the capacity to understand how emotions impact decision making. Problem solving is a complex and even multiphasic process. It is not about neutralizing emotion, but about using emotional information to enhance the process of recognizing a problem, feeling confident in one’s ability to work through it, defining the problem, generating a solution, and implementing the plan. The appropriate application of emotional information can help identify potential pitfalls, inspire the recruitment of help, and even expedite the solution by evoking feelings of confidence. Problem solving is about understanding the impact that emotions have on the decision making process and using those emotions most effectively.

Reality Testing is the capacity to remain objective by seeing things as they really are. This involves recognizing when emotions or personal bias can cause one to be less objective. Reality testing involves the active search for objective information to confirm, support, justify, and validate feelings, perceptions and thoughts. Strong reality testing skills allow one to keep things in the proper perspective and experience things as they really are, without fantasizing, daydreaming, or attaching wants, desires, and ideals to a context. An important aspect of reality testing involves the ability to concentrate and remain focused when presented with emotionally evocative situations. In essence, reality testing is all about perception, clarity, and objectivity.

Impulse Control is the ability to resist or delay an impulse, drive, or temptation to act. It involves avoiding rash behaviors and impetuous decision making. Impulse control entails a capacity for recognizing and accepting one’s desire to react without becoming a servant to that desire. Difficulties in impulse control are manifested by low emotional threshold, impulsiveness, loss of self-control, and unpredictable behavior.

Stress Management

The Stress Management Composite scale is comprised of Flexibility, Stress Tolerance, and Optimism. Collectively, this facet of emotional intelligence addresses how well one can cope with the emotions associated with change and unfamiliar or unpredictable circumstances, while remaining hopeful about the future and resilient in the face of setbacks and obstacles.

The Stress Management Composite scale is comprised of Flexibility, Stress Tolerance, and Optimism. Collectively, this facet of emotional intelligence addresses how well one can cope with the emotions associated with change and unfamiliar or unpredictable circumstances, while remaining hopeful about the future and resilient in the face of setbacks and obstacles.

Flexibility is adapting emotions, thoughts and behaviors to unfamiliar, unpredictable, and dynamic circumstances or ideas. This component of emotional intelligence refers to one’s overall ability to adapt and tolerate the stress that accompanies change. Flexible people are agile and capable of reacting to change with minimal adverse effect; they are open to and capable of change, and tolerant of new ideas, orientations, and practices.

Stress Tolerance involves coping with stressful or difficult situations and believing that one can manage or influence those situations in a positive manner. This component of emotional intelligence is multifaceted: one’s stress tolerance depends on being equipped with the necessary and relevant coping skills; maintaining a belief that one can handle the situation; and feeling confident that one can have a positive impact on the outcome. Stress tolerance is very much related to resilience and, when coupled with optimism, is a strong indicator of one’s ability to effectively deal with problems and crises (as opposed to surrendering to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness). When stress tolerance is low, anxiety is likely, which can have negative effects on well-being, concentration, and ultimately performance.

Optimism is an indicator of one’s positive attitude and outlook on life. It involves remaining hopeful and resilient, despite occasional setbacks. Optimism assumes a measure of hope in one’s approach to life. It is a positive approach to daily living and a significant component of resilience and well-being.Previously, the EQ-i included Happiness as one of the 15 components of emotional intelligence. The EQ-i 2.0 has been modified to include and view happiness more as a product of emotional intelligence and less as a contributing factor. That is, generally speaking, people who have reported higher EI scores on the EQ-i were more likely to also report higher happiness scores, and those with a lower EQ-i were more likely to report lower happiness scores. Given this trend, coupled with the fact that most coaches, consultants, and counselors find it difficult to directly coach to happiness, the decision was made to move happiness away from representing a component of EI to more appropriately represent a reflection of one’s well-being. As a result, the Well-Being Indicator was born. The exploration of the Well-Being Indicator included a detailed look into the relationship between one’s level of happiness and all the other facets of emotional intelligence. The result of a series of theoretical, practical, and empirical analyses identified Self-Regard, Optimism, Interpersonal Relationships, and Self-Actualization as key facets of emotional intelligence with direct connections to happiness and well-being that can be developed by effective coaching practices and positive change.

Each report will consist of a Happiness score. This score is generated in the same manner as all other EQ-i 2.0 subscales. Interpretation text is provided that incorporates feedback from the four aforementioned subscales (SR, OP, IR, SA) which are most intimately connected to happiness and subsequent well-being. As a result, the Well-Being Indicator presents a great place for addressing the correlates to happiness.

Happiness is an indicator of emotional health and well-being. It is characterized by feelings of satisfaction, contentment, and by the ability to enjoy the many aspects of one’s life.

The summation of the extent literature, client feedback, and empirical reviews resulted in modifications to the operational definition of Emotional Intelligence. Such changes have implications on the practical application of the EQ-i and, as a result, extensive work was undertaken to revise the factor structure underpinning the EQ-i. The resulting model of the EQ-i 2.0, yields a framework that is not only valid and reliable, but offers greater applicability in the practice of emotional intelligence.